Sherrill Wark blog October 11

What drives that inner urge for storytelling? In my October 7th blog, Why Do Writers Write, I ask that question because people want to know. It is not an easy answer, often illusive. But I put the question out there and decided to invite other writers to guest blog on my website and tell us what drives them to write.

Here we go with my first guest blogger.

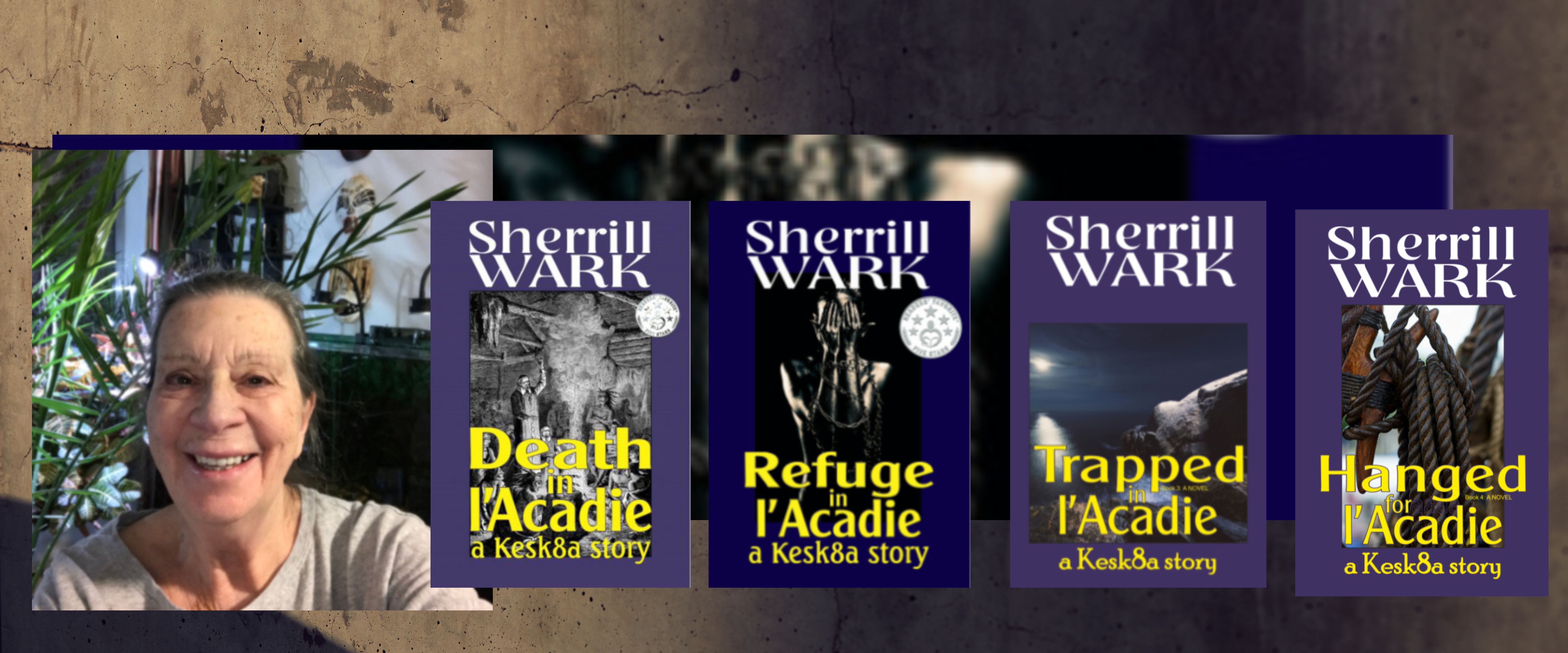

I take great pleasure in welcoming Sherrill Wark, a diversified writer of many genres to my blog page. Her Acadian Series is an emotional and heartfelt work of historical fiction featuring an Indigenous Mi'gmaw woman named Keskoua who endures the harsh environment and biases of early Canadian settlement (1678-1726) in Eastern Canada.

Marianne Scott. Writer/Author

In Sherrill Wark's own words, here is her story.

Why I Stopped Writing The Kesk8a Series after Number Four

Why would a horror novel writer switch to writing historical novels and end up writing a series of four of them and then be so “horrified” about the subject matter of the intended fifth one, that she stopped and went back to writing horror? Well, just draw yourselves in around my little campfire here and let me tell you a story.

Once upon a time, my father and his eldest sibling were doing the ancestry thing. This was before DNA was doing it for us, so hence the “once upon a time.” Research on ancestors in the “late twentieth century” (love it!), involved physical trips here, physical trips there, archives here, archives there. Both of them were elderly and hard of hearing but at least email was alive then. Dad finally connected with a cousin on the Wark side who provided a lot about that line; another cousin provided information that the Acadians (their mother’s side) had been keeping records since long before the Grand Dérangement a.k.a. the Expulsion of the Acadians a.k.a. where the Cajuns came from.

Great great plus grandfather Claude Guidry/Guédry had arrived, from France, in Acadia in 1670. His wife, great great plus grandmother Marguerite Petitpas, and her family were already here. Dad sent me a list of “Grandpa” Claude and “Grandma” Marguerite’s children. All eleven of them. Marguerite had two children from a previous marriage so that house must have been bedlam at times. Their ninth was my ancestor, Pierre.

Down at the bottom of that list, I spotted “child number xii.” Great great plus Grandpa Claude’s twelfth child: “Jeanne Guédry dit Laverdure, b. ca 1680, baptized 2 Jun 1681, St.John [sic] at Menagoneck, Acadia.” That’s funny, I thought, Keskoua and Claude’s daughter, Jeanne, was born before he married Marguerite in 1681. Oh, this is interesting.

Then I read the following paragraph: “In the book Acadian Church Records 1679–1757, it states the following about the birth of Jeanne Guédry: St.John [sic] at Menagoneck, June 2, 1681 Jeanne Guédry, daughter of Claude Guédry called la Verdure and Kesk8a Indian. Sponsors: Claude Petitpas and Jeanne de la tour [sic], wife of Martin. Note: Figure ‘8’ was used by French priest [sic] to indicate a sound in the Indian language sometimes translated as ‘ou’.”

I’m not sure if that’s when I started to cry or not. I was blown away, completely shocked and yes, “horrified,” that the first child of great great plus Grandpa Claude was listed last, not even as a separate entry, but as a twelfth child. Shouldn’t she have been listed first? Up there at the top? Incidentally, Claude and Marguerite took Jeanne in and raised her as their own. I assumed, then, that Keskoua must have died.

After I had that reaction to the “mystery” of why Jeanne wasn’t listed first and fully knowing the why (see, the word “Indian” above), that’s when I felt Keskoua’s hand reach out and squeeze my heart and I heard/felt the first few sentences in the book that was supposed to be just one book:

“When I told my friend Feather that I wanted to lay with the Father, she was horrified and told me I had to go to Confession right away or I’d go to Hell for sure. ‘And I told you,’ she added. ‘Don’t call me Feather no more. Call me Hélène.’

“‘Feathery Hélène. Hélène-y Feather.’ I loved to get her going so I could watch her eyes flashing at me like I was Father Soucy’s Devil that he was always talking about.”

Even though I was sure Keskoua had died, I decided to keep her “alive” as the actual, 1st Person storyteller so I could hear her and write down everything about those times. She was funny, funny, funny. That is, when she wasn’t reporting atrocities (that I double and triple checked). After that first unexpected joke of hers about laying with the Father, she wouldn’t shut up until I got to the end of book four. Death in l’Acadie, Refuge in l’Acadie, Trapped in l’Acadie, and Hanged for l’Acadie: the beginnings of the concept of residential schooling (brainwashing “the savages”), the slave trade, the Salem witch trials, piracy, destruction and war by New England, the kidnapping of “Indian” children into slavery…

It just kept getting worse.

The fifth book was supposed to be about the Scalp Proclamation. Yes, the “founder” of Halifax offered a bounty for every “half-breed’s” scalp (including fetuses if they had a scalp yet) to all comers and he brought people from England to settle there, on the land, no matter who was already there, and gave them a chance to make good money scalping people he didn’t want hanging around there anymore.

Within five years, England came up with the Expulsion (would have been book six) which meant that all of “the goddamned French” had to grab a bag—one bag—of belongings and get on the ships and off they’d go to Louisiana which was still owned by “the goddamned French.” I didn’t write about the Expulsion either. Everybody knows about that one. Right? One of Pierre’s sons or grandsons apparently complained so much by the time they reached Pennsylvania, they said, “Fine then. Off you go but to l’Assomption, Quebec. You aren’t going back to Nova Scotia.”

And that’s when I went back to writing horror. It’s a lot easier on the heart than writing about stuff the victors never told us about when we were in school.